Change Soon Come

Revamped and improved travel blog on the way! Stay tuned.

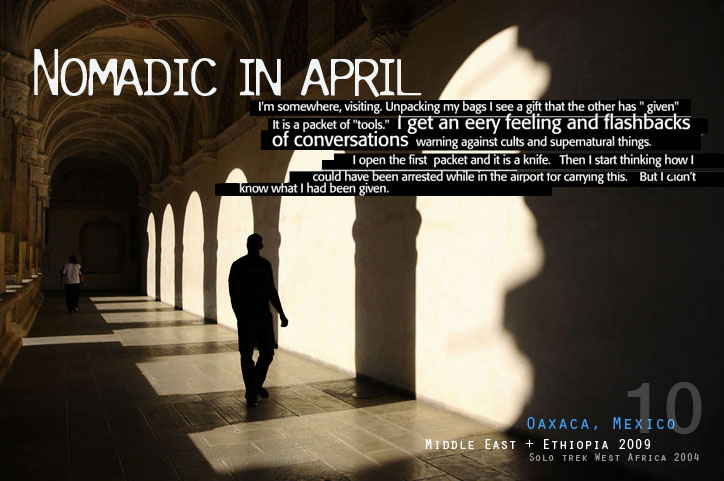

April Banks is on a mission to share a pot of tea in every country in the world. Follow her observations, reflections, misadventures and tea with artists.

Wednesday, November 09, 2011

Tuesday, June 15, 2010

WE RIDE Day 10, Mojave Desert

Today was by far the hardest. We left Ludlow, CA headed toward Needles, CA knowing we'd have to make it through 55 miles of 100+ degree heat with no shade or place to stop for food or water. What we didn't know was it was 10 miles of climbing. When we finally arrived 10 hours later we found ourselves at a reststop with no food or water. As usual, we become a spectacle...biking in the desert with 90 pounds of gear. But people offered us food and water like we were homeless.

Today was by far the hardest. We left Ludlow, CA headed toward Needles, CA knowing we'd have to make it through 55 miles of 100+ degree heat with no shade or place to stop for food or water. What we didn't know was it was 10 miles of climbing. When we finally arrived 10 hours later we found ourselves at a reststop with no food or water. As usual, we become a spectacle...biking in the desert with 90 pounds of gear. But people offered us food and water like we were homeless.

I crashed on a picnic bench while Kelly pulled the "aligator teeth" (the wires from all the burnt out tire trucks that are in the shoulders) out of her tires. After trying with no luck to hitch a ride to the next town, 36 miles away, we called CHP. And they came! Three cars came to transport us to Needles. They were very nice and agreed to be photographed and videod...as long as we made them look good. Lol. What a day. . .

Sunday, May 02, 2010

All my food from Oaxaca

I've just returned from the beautiful, beautiful city of Oaxaca in southern Mexico! And no I didn't go because there is chocolate in every thing from savory sauces to hot chocolate with water. I love chocolate, but I am interested in other things! I have to say this may be the most adventurous I've ever been with food while traveling, although I stopped short of the grasshoppers.

Oaxaca is known for it's food. You can take cooking classes while you are visiting or you can just try everything you see! For a more articulate summary of Oaxacan food: Cuisine of Oaxaca

Oaxaca is known for it's food. You can take cooking classes while you are visiting or you can just try everything you see! For a more articulate summary of Oaxacan food: Cuisine of OaxacaSaturday, May 01, 2010

Friday, October 16, 2009

New Years Day - Sept 11

I finally had a chance to visit an Orthodox Christian church on New Year's Day in Addis. I was moved by the stillness and the trance-like intensity of everyone present. (This post should replace all negative statements about angry bees I may have mentioned in an earlier post. . . although I have to say that from the outside the sound coming from the speakers is still really bad! But I digress, this is about the beauty of the prayer ceremony)

Selam and I didn't make the 6am start, but we did arrive near the end of the service. . . at 12 noon! We went to the largest, newest, shiniest, most humongous church in Addis. By the time we arrived many people had left, but those who remained were in either resting positions on the floor, kneeling or standing with palms raised to the sky. We ascended to the balcony so that I could take photos without feeling invasive. I was mezmerized by the massive scale and decadence of the church's interior. We waited for a while and another prayer service began. The priests, speaking in Gi'iz—the language of the church, led the audience through several prayers. The call and response rises and falls and sent chills down my back.

Listen to this clip of one of the prayers:

Selam and I didn't make the 6am start, but we did arrive near the end of the service. . . at 12 noon! We went to the largest, newest, shiniest, most humongous church in Addis. By the time we arrived many people had left, but those who remained were in either resting positions on the floor, kneeling or standing with palms raised to the sky. We ascended to the balcony so that I could take photos without feeling invasive. I was mezmerized by the massive scale and decadence of the church's interior. We waited for a while and another prayer service began. The priests, speaking in Gi'iz—the language of the church, led the audience through several prayers. The call and response rises and falls and sent chills down my back.

Listen to this clip of one of the prayers:

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Saturday, September 05, 2009

Goats at the Gas Pump

Animals and their humans. . .yes, that's right. As my bus passed by, I wasn't fast enough on the draw, to photograph the pack of goats milling around the gas pumps at an empty gas station. No cars, just goats. In general it seems animals rule. On any road trip it's a given that half the mileage will be spent crisscrossing the road avoiding mildly herded packs of co-mingled donkeys, goats, cows, horses and the occasional camel. You may see a barely tail high boy traipsing along nearby, jumping out at the last second to appear to be in control of his animal nation. This is the ire of most drivers whose horns are honking more than they are silent. Brake repair is the business in which to invest.

The roving animals, however, do not inspire the drivers to drive slower or more cautiously. Instead it becomes a live game of frogger. Not for the faint of heart, especially when it's a giant bus barreling down a curvy, misty mountain pass. This would explain the dozen or so horrifically smashed vehicles from accidents long since past. Most had become part of the landscape with plants growing out of the windshield and rusted bodies to match the red dirt. I wondered why no one came to claim or moved the vehicles. One passenger mini-van still sat dead center of the road, it's guts hanging out and personal items strewn across the road. Very sobering, thankfully even for the bus driver, who crossed his head and heart and slowed his roll.

Road trip!

Tuesday, August 25, 2009

Lost in Translation

During the days of the week I walk around Addis, people watch, sit at cafes sipping tea, (coffee when there is electricity) visit bookstores, venture onto minibus taxi rides, endure the ultimate patience test for 80s era internet speed at internet cafes and wherever else the wind blows me. Since I pass as Ethiopian, I mostly just blend in. . .until. . .

Usually goes something like this. . .

I enter one of the many glazed glass office looking buildings that are malls. Before entering I encounter either an airport style security scanner, the walk through kind and the bed scanner or a pair of guards wielding a magic wand. First we establish that I cannot speak Amharic. This after something is asked of me while I’m being felt up, head to toe and purse searched. (I’ve have enough x-rays in me enough for six lifetimes. hmmmm. . .I wonder if the side effects of this is considered or studied. . .not to mention the psychological effect.)

All I can understand is camera. In English I say “I don’t speak Amharic” If I say it in Amharic, then I’ll get a response in Amharic and we are back to square one. Consistently, I get this look. Now normally I am quite happy to blend in and not be stared at like many other places I’ve traveled. But this look. . .it’s a look mixed of what do you mean you don’t speak Amharic and What a shame that you have gone away and lost your culture. I’m always waived through with a look of pity and some murmurs as I walk away. In these situations I don’t bother explaining that I’m not Ethiopian. Although one woman told me I shouldn’t say I don’t speak Amharic, say I’m not Ethiopian.

I save that for the people I have conversations with, which goes something like this. . .

something, something, something (in Amharic)

Oh, I'm sorry, I don't speak Amharic.

eh? Oh you look Habesha. So is your father Ethiopian?

nope

Grandfather?

nope

Your mother?

nope

Your mother?

nope

Are you Jamaican?

nope

Are you Jamaican?

nope

Cuban?

nope. American.

nope. American.

American? But you are from here?

nope. American for many generations.

(still don't know how I can be Jamaican or Cuban but not American when it's the same story as the U.S.)

Also lost in translation. . .

Sudden in-take of air

What? Did I say something shocking, something wrong? I ask again.

Sudden in-take of air. . . with an ever so slight up knod of the head or lift of the eyebrow with the mouth just barely parted.

Oh now I get it. That sound I know as shock or surprise is an affirmation, yes, or yes continue. Very confusing at first.

Ish, ish, ish. . .also yes, continue

Hand shake, shoulder tap

Triple kiss, left right left cheek, no! right left right cheek.

All greetings which one do I do when?!!

Sunday, August 23, 2009

Descent into a crater

This weekend Selam and I went hiking. We survived a death ride to a lake in a crater. It's an amazing place and the first time Selam had been. We were in Wenchi, a remote village just a short drive from Addis. We climbed down a no path, path on a brilliant green carpet mountain to the lake. A "search party" came after us. By the time we came back up we had collected a pack of youngsters on horses waiting for the moment we'd give up and beg for a ride. But we perservered in the high altitude and vertical climb on dewy grass with all the wrong shoes. Truly an amazing place. It's winter here and quite a shock to my system after the Middle East! But oh so beautiful.

Oh, when we stopped at the tourist center to collect our guide, one little boy came to the car to ask for a pen. We couldn't find any so we gave him a piece of candy. He summoned alllllllll his friends and they rushed the car, and then followed us to the start of the path.

Narcissus the bird

It took me a minute to realize what was happening. I sit lounging in one of the many living rooms, reading "The Witch of Portabello." There is a persistent tapping on the window. A bird is attacking its reflection! The windows have a mirror glaze. But you have to understand this bird is going to kill itself, he's pecking so hard. He hops away and flutters his wings angrily and then dives back in for another round of pounding. He keeps this up for 15 minutes at a time and has come back on multiple days. He's a cute little bird. Maybe he's been listening to the screeching at the church too. . .

Saturday, August 22, 2009

Angry Bees

I woke up at 3am. I was having angry dreams about people stealing from my massive pile of french fries. but that's not important. What woke me up is what was making me have angry dreams. And how do I describe this without sounding like a hater. I'll start by saying that I've been told that if I go to an Ethiopian Orthodox Christian church I will be amazed by the beauty of the ceremony and the singing. I'm looking forward to that experience. In the meantime. . . I am being tortured nightly by the nail-on-chalkboard screeching of the really bad speakers that broadcast the prayers from the church across the way. Last night I woke up at 3am to this ongoing sound.

Imagine an auctioneer on a really bad microphone combined with a massive swarm of angry bees buzzing a centimeter from your ears. This went on and on and on. It was especially bad last night because it was the end of the fast. Which coincidentally is also the start of Ramadan. And on that note, I am used to this, coming from the Middle East, where the call to prayer is broadcast from mosques. But never at an ungodly hour like 3am and its melodious and lasts 2 minutes tops.

Ok, now that I've vented, I'm going go to eat some french fries. I'll revisit this with a new attitude after my visit to a church. By then I'll have a beautiful image to replace the auctioneer and angry bees.

Making Injera

It may look easy, but it really isn’t. I’ve made my share of pancakes, but spreading the injera batter in a large circle, over a very hot clay plate, evenly and quickly is harder than you might think. Sadly mine ended up in the reject pile. Not perfect enough. Fit for firfir, maybe? (In case you didn’t know, injera aka breadforkplatenapkin, is the staple food that is eaten with everything.)

The reject pile. . .

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

Stairway to Heaven

Addis is the same time zone, so I'm up and about by 11am. I meet Selam at her new office and we walk to lunch for Habesha food! What a way to start my trip. I arrived during the fast, during which no meat or dairy is eaten.

But wait, let me back up and tell you about my accent to heaven also known as the Minaye's house. Thank god I just came from hilly Amman where there are stairs in the side of every hill. So I was well prepared for the climb to "my suite" on the 5th, 7th floor? I lost count. . .wow.

Tuesday, August 18, 2009

Ethiopia Day 1

I almost missed my flight! I had the wrong day. That's what happens when you lose track of day and time. It was only because I was telling Susu how I reminded Selam that Tuesday at 3am is really like Monday night so don't forget me! Thankfully I realized this at 10am and my flight was for 10pm. So I left Jordan in a whirlwind and then suddenly. . .I'm in Ethiopia.

But that four hour transition from Amman to Addis Ababa is one to be remembered.

I arrived at the airport after an Arabic lesson and date proposal from my taxi driver. I escaped hastily and went inside. At this airport you go through security before going to your airline to check in. I arrive at the check in counters and can't find BMI on any of the signs. So I ask three different people and finally I'm told that I'm four hours early. I say "no way! my flight leaves in an hour. Where is the counter for BMI?" Oh well they don't have a counter yet. Just go sit over there and someone will come for you.

This is truly a first. So I sit and decide to use the airport wireless to upload some pics. Then a BMI agent comes over and asks me if I'm flying to Addis. I say yes, and he says come with me. We go to the check in counter and the "interrogation" begins. Why are you going to Ethiopia? Are you Ethiopian? How long are you staying? When did you arrive in Jordan? Obviously I looked confused and or annoyed and he smiled and said with his British accent, "This is for security purposes." I said, mhmmm and asked if I'm the only passenger. He said yes. Now I'm suspicious! I asked, am I the only person on the plane?! Is it a regular commercial jet? No you are not the only passenger. There are 30 or so other passengers coming from London. Hmmmmm. Very strange.

Next I go through immigration. They look at me, look at my passport, look at me. Are you Ethiopian? no. Is your father Ethiopian? no. Is your grandfather Ethiopian? no. Why are you going to Ethiopia? I'm thinking to myself why are there flights to Ethiopia from Amman if it seems so unusual? How long were you in Jordan? one month. Luckily I was at exactly one month after coming back from Syria. Otherwise I would have been over my 30 day visa and who knows what suspicion that would have caused. The officer smiles, stamps my passport and waves me through.

But that four hour transition from Amman to Addis Ababa is one to be remembered.

I arrived at the airport after an Arabic lesson and date proposal from my taxi driver. I escaped hastily and went inside. At this airport you go through security before going to your airline to check in. I arrive at the check in counters and can't find BMI on any of the signs. So I ask three different people and finally I'm told that I'm four hours early. I say "no way! my flight leaves in an hour. Where is the counter for BMI?" Oh well they don't have a counter yet. Just go sit over there and someone will come for you.

This is truly a first. So I sit and decide to use the airport wireless to upload some pics. Then a BMI agent comes over and asks me if I'm flying to Addis. I say yes, and he says come with me. We go to the check in counter and the "interrogation" begins. Why are you going to Ethiopia? Are you Ethiopian? How long are you staying? When did you arrive in Jordan? Obviously I looked confused and or annoyed and he smiled and said with his British accent, "This is for security purposes." I said, mhmmm and asked if I'm the only passenger. He said yes. Now I'm suspicious! I asked, am I the only person on the plane?! Is it a regular commercial jet? No you are not the only passenger. There are 30 or so other passengers coming from London. Hmmmmm. Very strange.

Next I go through immigration. They look at me, look at my passport, look at me. Are you Ethiopian? no. Is your father Ethiopian? no. Is your grandfather Ethiopian? no. Why are you going to Ethiopia? I'm thinking to myself why are there flights to Ethiopia from Amman if it seems so unusual? How long were you in Jordan? one month. Luckily I was at exactly one month after coming back from Syria. Otherwise I would have been over my 30 day visa and who knows what suspicion that would have caused. The officer smiles, stamps my passport and waves me through.

So I go to my gate and wait alone. There is no one around. The boarding time has come and gone. There are no signs to update me. Finally the same counter agent comes to walk me down the jetway to the plane. I say "well aren't you just everywhere" and he smiles and says, "yes I am."

So I go to my gate and wait alone. There is no one around. The boarding time has come and gone. There are no signs to update me. Finally the same counter agent comes to walk me down the jetway to the plane. I say "well aren't you just everywhere" and he smiles and says, "yes I am." The flight is short—four hours. I wake up and enter a new world. Its 3am and I stumble off the plane into the immigrations area. There are only a few agents waiting. Most hurry and sit up from their sleeping positions. No one is there to guide us, so I go to the Immigration desk and the officer is almost done processing me and asks for my visa. I say I want to buy one and she says oh, you have to go to that window.

The flight is short—four hours. I wake up and enter a new world. Its 3am and I stumble off the plane into the immigrations area. There are only a few agents waiting. Most hurry and sit up from their sleeping positions. No one is there to guide us, so I go to the Immigration desk and the officer is almost done processing me and asks for my visa. I say I want to buy one and she says oh, you have to go to that window.So I go to the other window, wait in line and discover that they only take US dollars or Euro for the visa payment. I had planned to get US dollars, but because I had to rush to leave, I didn't have time and figured the Jordanian dinar is stronger, surely they'll take it. So they send me to the exchange counter. The old man behind the glass looks at my dinars, looks at me, clicks his tongue, waves me away and turns his back. I say "excuse me!" I need to exchange some money to pay for my visa. He says "I don't take that" I say well what shall I do? He says go to that window over there, they'll take it. I go and no one is there. I wait. No one. I go back to the visa window, and the woman says, "oh there is someone there. just bang on the window, they are asleep under their desks." I go back, bang on the window, yell through the hole. No answer.

By now, there is another family in the same situation as me, they have British pounds. I go back to the visa window, the agent says, did you bang hard? I said no one is there. She says, yes there is. There is a jacket on the chair. Oh my god! it's now 3:30 am. My friend is waiting in arrival. I feel like I'm running in circles. I go and ask the visa agents what can I do? They said is there someone here to meet you? Get some money from them. I said my friend is Ethiopian, she won't have US dollars or Euros. They said take her Ethiopian birr to the exchange and get US dollars, then come back. So let me get this straight, you'll let me walk out through immigrations and customs without visa to ask for money to pay for my visa because someone is sleeping under their desk? Yes ma'am, you have five minutes.

By now, there is another family in the same situation as me, they have British pounds. I go back to the visa window, the agent says, did you bang hard? I said no one is there. She says, yes there is. There is a jacket on the chair. Oh my god! it's now 3:30 am. My friend is waiting in arrival. I feel like I'm running in circles. I go and ask the visa agents what can I do? They said is there someone here to meet you? Get some money from them. I said my friend is Ethiopian, she won't have US dollars or Euros. They said take her Ethiopian birr to the exchange and get US dollars, then come back. So let me get this straight, you'll let me walk out through immigrations and customs without visa to ask for money to pay for my visa because someone is sleeping under their desk? Yes ma'am, you have five minutes.So I do just that. Meet my friend's mother get Ethiopian birr from her (nothing like asking for money from someone you've just met, but its now 4am and I just want to leave) and return to the exchange window. Sorry, we don't take birr. WHAT?!!!! you don't take your own money? Are you serious? I go back to the visa window, tell them what's happening, give them the poor sad tired eyes and ask them what I can do. Three agents huddle together, speaking in Amharic and come up with a solution. One agent rights out a "receipt" and says take this, leave your passport here and when you get US dollars or Euros, come back to the airport for your visa. I said "what? are you serious!" I can't leave without my passport. The agent assured me it was fine, the passport would be safe and secure and this was the only solution since someone was sleeping under their desk. I pause and consider the time and that my friend's mom is waiting. I take the receipt and slowly leave. As I get to baggage claim I seem a British woman from my flight. Yes! I ask her if she has US dollars or Euro that I can for exchange my borrowed birr. She agrees but insists on giving me the $20USD, yes, all of this for $20 at 4am.

I take the $20, walk back through customs and immigration, the wrong way! Where's the security? And retrieve my passport. Cheers all around. The agents asked where I found it. I told them about the random act of kindness. They said, "ooooooooh! she must be very rich."

Note for future travellers: always keep US dollars on hand.

Yeah! I made it. Just like that, I'm on another continent. New language, new money, new people, new way of life. The second adventure begins!

Monday, August 17, 2009

These are a Few of My Favorite Things

I love the desert! I think I'm borderline obsessed with it. The stillness and endlessness magnifies how small we are as human beings. The sublime sunrise and sunset when all is perfectly quiet. I have the utmost respect for people, plants and animals who navigate the extreme conditions. The only way to survive is to be in tune with every sign and signal from the sun, to the wind to the stars. One of my ultimate dreams is to make a trek with the esoteric Tuareg (nomadic people of North African) through the Sahara desert.

In the meantime, I took an overnight trip to a Bedouin camp in the Jordan desert. Not nearly as grueling and adventurous, but amazingly beautiful still. Wadi Rum is in southwest Jordan and about a two hour drive from Petra. I went with fellow instructors Mark and Susu and we began our day hiking through Petra. After climbing and descending 1000 "stairs" to the top of Petra we were whisked away by our driver to catch the sunset at our campsite. We met our camp guy at the entrance to the area and he drove us winding and spinning through the sand to our campsite. . .for tourists. We arrived just as the sun was disappearing over the rocky cliffs to a camp full of French tourists. I have to say I was disappointed as I imagined this experience of me against nature! So I dragged my bedding away from the rows of tents and slept under the stars. So beautiful. So beautiful. I tried to stay awake all night, but the hike in sweltering heat and direct sun soon caught up and rocked me to sleep. The next morning I awoke before sunrise and before the camp was awake. The red sand and cliffs changed colors as the sun rose higher and higher. It was so quiet and still, I felt like the only person on earth.

I love the dessert! Other favorite deserts: The lencois dunes in Maranhao, Brazil; The Dogon villages in Mali.

Thursday, July 23, 2009

A Song for Baghdad

In Amman, we held class at the sports club at the Wehdat refugee camp. Our photography students were only a small portion of all the kids and adults attending the center. Everyday we were mobbed by screams, sad eyed, angle headed pleading and leaps for your cameras. I fell for the act the first day, but quickly learned that little people should not be allowed to play with very expensive cameras. But because we had fallen for the act the first day, everyday was a repeat of the begging and mobbing. Regardless, they were very cute inspite of their persistence. On this particular day a group of Iraqi students decided to sing a song about Baghdad for Susu. Notice the performer in the middle!

And because they knew that we were recording them, they insisted on seeing the video.

Giggles, giggles, all around.

Monday, July 06, 2009

Crossing Borders, Again. . .

We plan to spend 10 days in Lebanon, but have no real “plan” for exactly how we are going to get there and only a vague plan for where we will stay. The night before we leave I go to an internet café and print out the Lonely Planet guide for Beirut. Our friend’s sister who has been our host and guide in Damascus calls a taxi friend that she has used to make the trip. He is not available and sends a friend. We are to meet him near the old Roman columns in a white car at 7am. How about that? When was the last time you crossed a border with a random taxi that you find waiting for you on the side of the road at dawn.

The drive is beautiful and I strain to stay awake. We are still jetlagged as we’ve been through four countries in the last five days. But I’m determined to stay awake. We quickly reach the border and first go through exiting in Syria. Then we drive on a ways and have to go through immigrations/entering for Lebanon. (Watch the Syrian Bride and you’ll get an idea of how wide the border crossings are.) Because Susu and I have American passports we have to get out each time and go inside to pay for our visas and have our passports stamped. It’s all a bit murky as to what we are supposed to do. So the taxi driver hastily rushes us through pointing us towards the counters we need to visit. Driving in a Syrian taxi he can cross the borders, but must also show his papers and that he can legally take us.

When we go through Lebanese immigrations, it is calm in comparison to the entry into Syria. When we go to buy our visa, they tell us we need to exchange our US dollars for Lebanese money. Thankfully Susu was on top of the exchange rate and acutely alert, while I was foggy and disoriented. We asked where we could exchange our money and the immigrations officer turned and pointed out the door to. . .a man. . .standing. . .behind a hole in the border fence!!! That’s right! I couldn’t believe it. I was in the parking lot halfway between the car and the fence trying to keep an eye on our luggage, but also staying with Susu to make sure we weren’t getting ripped off. For whatever reason, the taxi drivers ALWAYS feel obliged to insert themselves in all transactions, which leaves us feeling suspicious. As if exchanging money through a hole in the fence isn’t already suspect enough. As expected, mr. money changer decides to test our math skills and does some fancy calculations that leave us scratching our heads and wondering if he thinks we are really that dumb. Battle number nine ensues and Susu emerges victorious.

We get back into our taxi, our other hijabi passenger, plugged into her ipod, waits expressionless. . . and we are off. Just like that, we are now in Lebanon. The landscape becomes greener and more lush with each turn in the winding road. We are approaching the coast and the dry dessert air first becomes cooler as we go up over the mountains and then becomes thick and humid as we descend into the sprawling outer limits of Beirut.

Susu and I have spent two days in the labrynthian old Damascus and we are moving on to Beirut. It’s a only three hour ride from the capital city in Syria to Lebanon. I’m excited and anxious to see Beirut. I’ve heard so much about it being the Paris of the Middle East which is an image that is exactly the opposite of my mental image of Beirut, provided courtesy of the war-machine media. I first heard about Beirut in 1985 during the hi-jacking of TWA 847. At such a young age, all references to Beirut were drawn in my memory as a city far away, were people were stuck on a plane. Really, what I remember is an image of a runway with a plane and some people on the ground. This is such a vivid image and I see it in black and white. So I wonder if it was a newspaper article or just my imagination. Whatever the case, I never envisioned Beirut as a whole city full of life, and color and people and love. Though Beirut has seen years and years of civil war and political instability, it is a city that continues to thrive and negates all stereotypes of what is the Middle East.

We plan to spend 10 days in Lebanon, but have no real “plan” for exactly how we are going to get there and only a vague plan for where we will stay. The night before we leave I go to an internet café and print out the Lonely Planet guide for Beirut. Our friend’s sister who has been our host and guide in Damascus calls a taxi friend that she has used to make the trip. He is not available and sends a friend. We are to meet him near the old Roman columns in a white car at 7am. How about that? When was the last time you crossed a border with a random taxi that you find waiting for you on the side of the road at dawn.

Up to this point we’ve had battles with all our taxi drivers who feel the need to provide us with information that is not exactly true. I’m not saying they were lying, just re-forming what is necessary information to benefit themselves. Yeah, right. So we find out that we are sharing a taxi and drive to another part of town to pick up a student who is attending a university in Beirut. The charge for the shared taxi depends on, get this, where you sit and how many people are in the car. If you ride shotgun, it costs more! So we take the back seats, which are a safer distance from the inevitable come-ons of the driver. All cars are supposed to have AC which is why you take one instead of a bus. Oh and all the taxi cars are very modern four door sedans, Toyotas or Hyundais, so there is no issue with them being unreliable. We’ve negotiated the price of $30 each and are off on our journey.

The drive is beautiful and I strain to stay awake. We are still jetlagged as we’ve been through four countries in the last five days. But I’m determined to stay awake. We quickly reach the border and first go through exiting in Syria. Then we drive on a ways and have to go through immigrations/entering for Lebanon. (Watch the Syrian Bride and you’ll get an idea of how wide the border crossings are.) Because Susu and I have American passports we have to get out each time and go inside to pay for our visas and have our passports stamped. It’s all a bit murky as to what we are supposed to do. So the taxi driver hastily rushes us through pointing us towards the counters we need to visit. Driving in a Syrian taxi he can cross the borders, but must also show his papers and that he can legally take us.

Lines? What lines? Pushing and shoving and yelling is the only way to get through immigrations.

When we go through Lebanese immigrations, it is calm in comparison to the entry into Syria. When we go to buy our visa, they tell us we need to exchange our US dollars for Lebanese money. Thankfully Susu was on top of the exchange rate and acutely alert, while I was foggy and disoriented. We asked where we could exchange our money and the immigrations officer turned and pointed out the door to. . .a man. . .standing. . .behind a hole in the border fence!!! That’s right! I couldn’t believe it. I was in the parking lot halfway between the car and the fence trying to keep an eye on our luggage, but also staying with Susu to make sure we weren’t getting ripped off. For whatever reason, the taxi drivers ALWAYS feel obliged to insert themselves in all transactions, which leaves us feeling suspicious. As if exchanging money through a hole in the fence isn’t already suspect enough. As expected, mr. money changer decides to test our math skills and does some fancy calculations that leave us scratching our heads and wondering if he thinks we are really that dumb. Battle number nine ensues and Susu emerges victorious.

We get back into our taxi, our other hijabi passenger, plugged into her ipod, waits expressionless. . . and we are off. Just like that, we are now in Lebanon. The landscape becomes greener and more lush with each turn in the winding road. We are approaching the coast and the dry dessert air first becomes cooler as we go up over the mountains and then becomes thick and humid as we descend into the sprawling outer limits of Beirut.

We have a contact in Beirut, a friend of a friend who is supposed to meet us and take us to our room at a dormitory at the Arab University. The taxi driver drops of the other passenger and we continue on through one-mile-an-hour bumper to bumper traffic to the other side of the city. We aren’t sure where we are going and the taxi driver calls our friend for directions. We are sitting at an impasse where officers are trying to direct the laneless traffic. Our Beirut contact finds out our location and says he’ll come meet us. And not a moment too soon! He drives up, just as the traffic officers pull our taxi driver off the road and out of the car. We find out he’s not licensed to drive this far into the city! As a Syrian driver, he’s supposed to drop us off at the border and we take a local taxi into the city. We felt bad leaving him in the situation, but what can you do? So we hopped out and got into the other car and were whisked off to the dormitory. . .which had no vacancy and no record of our “reservation.”

This is gonna be good.

This is gonna be good.

Welcome to Beirut!!!

Wednesday, July 01, 2009

note to self: Forget Everything You Know

>>view of Jebel Amman, from my apt window in Jordan

My latest travel adventures have begun. I am traveling with friend and fellow artist, Susu, around the Middle East—Dubai, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and Ethiopia until late September. I like to believe that when I travel to new places, I have no expectations. At least I've decided not to believe the media images that we are fed in the U.S.

But what image do I have to replace that "non-image?" I'm surprised every time.

Looks like once again taxis will be starring prominently in my stories.

I'm now in Amman, Jordan and week one of Project Souarna is complete. I'll be working backwards and forward filling in the daily details to catch up on posts. So much to share already at the end of week three.

Stay tuned!

ab

(this was my first post on July 25, but I'm gonna do some time travel and post things according to the date they happened. can you follow me?)

>>view of Jebel Amman, from my apt window in Jordan

My latest travel adventures have begun. I am traveling with friend and fellow artist, Susu, around the Middle East—Dubai, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and Ethiopia until late September. I like to believe that when I travel to new places, I have no expectations. At least I've decided not to believe the media images that we are fed in the U.S.

But what image do I have to replace that "non-image?" I'm surprised every time.

Looks like once again taxis will be starring prominently in my stories.

I'm now in Amman, Jordan and week one of Project Souarna is complete. I'll be working backwards and forward filling in the daily details to catch up on posts. So much to share already at the end of week three.

Stay tuned!

ab

(this was my first post on July 25, but I'm gonna do some time travel and post things according to the date they happened. can you follow me?)

Sunday, April 27, 2008

Thursday, December 02, 2004

Almost. . .

I now know that I got sick in Mali (or even before in Burkina Faso), but the symptoms didn't show until I arrived in Dakar.

My flight arrived around 1am on Wednesday and by 10am I was on my first tour of Dakar, lead by Karim Abdul. We walked and walked and walked from the University of Dakar to the beach to the president's palace and through all the major markets. It was hot and we were walking fast. By 3pm I suddenly felt very tired and we headed home. The next two afternoons I walked around the city escorted by two Gabonese students.

Friday night I stood in the kitchen, eating and talking to my hostess. As I ate, I began to sweat and I felt like I was going to faint. I went to my room to lay down. In the middle of the night I woke up to turn off the fan because I was cold. I thought, this is amazing, the first cool night since I've been in Africa. When I thought about it again, it seemed too strange. I looked at the temperature on my travel clock. It was 85 degrees. Oh boy! I'm sick!

There was nothing I could do so I lay there until morning. By then I was freezing and shivering in spite of the rising morning temperature. I told my hostess I thought I was sick. By mid morning she and the housekeeper, Cora decided I had the symptoms of malaria and should go to the hospital. At this point I was feeling delirious and could barely stand. I was sweating profusely and felt very weak. With Cora and the house guard flanked on each side, we slowly made our way to the hospital four blocks away.

It was a nightmare at the hospital. I was miserable and could not sit up. People in far worse condition than me were coming in. It was a depressing scene. (I had visited one other hospital and an AIDS hospice in Ghana. We have it made in the U.S.) I was dreading the wait, but at the same time too delirious to really worry about it. Five hours later, I was finally seen by a what I assume was a doctor. I was prepared to use my limited french to describe how I was feeling. But Cora did all the talking, in wolof. So I couldn't understand what she and the doctor were discussing. After noting my profuse sweating and taking my blood pressure, I was diagnosed with malaria and given a prescription for several shots. No exam. My temperature wasn't taken. No blood tests.

In Senegal, the patient is required to go to a pharmacy to get their own medication and bring it back for the nurse to inject. By the time Cora came back with my prescription, adrenaline kicked in and my head was mometarily clear. I was trying not to panic. I had no idea what they were treating me for, nor what medication they were giving me. I could only assume, it was for malaria, since Cora was certain that that is what I had. I pulled out my french phrasebook and put together a question about the medication they were going to give me and if it would have a contra-indication with the malaria pills I had already been taking. When I was called in, Cora went with me. In french, I tried to explain to the nurse that I was taking this medication (I showed it to her) and I wanted to make sure it would not have a bad reaction. She shoved the pills out of my hand and said "Non" loudly and forcefully. She rambled off something in wolof. She tried to hold me down in the chair to give me the injection. I snatched away and again tried to explain. She and Cora both kept telling me no. After a big enough fuss, a man who spoke English came in and translated what I was trying to say. They decided not to give me the shot for malaria, but still gave me a shot, that I later found out was for pain. I was never able to find out exactly what it was.

We made it back to the house and I collapsed in the bed. By late evening, I was beginning to doubt that I had malaria. One of the main symptoms is that your whole body is racked with excrutiating pain. I was weak and dizzy, but not in pain. My hostess decided to call a private doctor she knows that speaks English. (I'm not sure why she didn't mention this before my horrific hospital experience.) We took a taxi and went to her home office. After explaining my symptoms she did a full exam and diagnosed me with a gastrointestinal infection. She prescribed an antibiotic and told me to come back if I wasn't feeling better in two days. Two days later I went back and she sent me to have lab tests and a chest x-ray because I was having trouble breathing. Because getting a taxi and going out took a lot of energy, I decided to wait two days to see if I felt any better. Two days passed with no improvement. I went to the lab and had tests done. Sparing all the gorey details, by the end of the day I had the results and returned to the doctor's for her analysis of the report, which was written in french. The diagnosis: amoebic dysentery. Sounds horrible. Well it was. With the proper diagnosis, she changed my prescription and added iron to the list of pills, since by then I was anemic.

With the change of medication, I felt even worse. Now on top of being weak, sweaty, dehydrated and unable to eat, I was double over in pain. Oh, and just as a safety measure, I was also given a 3-day malaria pill treatment. I was taking so many pills throughout the day that it became my occupation. Some pills required that I eat, which was impossible. I was hating food. It was a battle to keep up the pill regiment. But I knew that I wouldn't get better if I didn't.

By the time I got the proper diagnosis, a week had past. I did nothing all day but lie in bed and when I could focus, I would read. I read any and everything. Whatever was available just to keep from going crazy. By the middle of the second week, I was feeling better, but still too weak to do anything. I knew that I wouldn't have the energy to pack myself into a stiffling hot bus and trek to the next city. I decided it was best to go home. Feeling both disappointed and stircrazy, I knew it would be better to go home and finish recovering there. At least I wouldn't have to be paranoid about everything I ate and drank. After two and half weeks, I was well enough to make the long flight home.

My original plan was to stop in Paris for a few days on the way back. This would have broken up the long flight, but because I was sick, it was condensed into one day. Well, it would have been if I hadn't missed my connecting flight in Paris. I flew from Dakar to Lisbon to Paris to Amsterdam to San Francisco. The flight from Lisbon was two hours late so I just missed the connecting flight in Paris. I stayed the night. I guess I can claim to have been to Paris but I was too tired (and cold) to go out, so my total Parisian experience was a one hour train ride from one airport to the other and the shuttle ride to my hotel. I like what I saw. I'll have to return to both Paris and Senegal.

My flight arrived around 1am on Wednesday and by 10am I was on my first tour of Dakar, lead by Karim Abdul. We walked and walked and walked from the University of Dakar to the beach to the president's palace and through all the major markets. It was hot and we were walking fast. By 3pm I suddenly felt very tired and we headed home. The next two afternoons I walked around the city escorted by two Gabonese students.

Friday night I stood in the kitchen, eating and talking to my hostess. As I ate, I began to sweat and I felt like I was going to faint. I went to my room to lay down. In the middle of the night I woke up to turn off the fan because I was cold. I thought, this is amazing, the first cool night since I've been in Africa. When I thought about it again, it seemed too strange. I looked at the temperature on my travel clock. It was 85 degrees. Oh boy! I'm sick!

There was nothing I could do so I lay there until morning. By then I was freezing and shivering in spite of the rising morning temperature. I told my hostess I thought I was sick. By mid morning she and the housekeeper, Cora decided I had the symptoms of malaria and should go to the hospital. At this point I was feeling delirious and could barely stand. I was sweating profusely and felt very weak. With Cora and the house guard flanked on each side, we slowly made our way to the hospital four blocks away.

It was a nightmare at the hospital. I was miserable and could not sit up. People in far worse condition than me were coming in. It was a depressing scene. (I had visited one other hospital and an AIDS hospice in Ghana. We have it made in the U.S.) I was dreading the wait, but at the same time too delirious to really worry about it. Five hours later, I was finally seen by a what I assume was a doctor. I was prepared to use my limited french to describe how I was feeling. But Cora did all the talking, in wolof. So I couldn't understand what she and the doctor were discussing. After noting my profuse sweating and taking my blood pressure, I was diagnosed with malaria and given a prescription for several shots. No exam. My temperature wasn't taken. No blood tests.

In Senegal, the patient is required to go to a pharmacy to get their own medication and bring it back for the nurse to inject. By the time Cora came back with my prescription, adrenaline kicked in and my head was mometarily clear. I was trying not to panic. I had no idea what they were treating me for, nor what medication they were giving me. I could only assume, it was for malaria, since Cora was certain that that is what I had. I pulled out my french phrasebook and put together a question about the medication they were going to give me and if it would have a contra-indication with the malaria pills I had already been taking. When I was called in, Cora went with me. In french, I tried to explain to the nurse that I was taking this medication (I showed it to her) and I wanted to make sure it would not have a bad reaction. She shoved the pills out of my hand and said "Non" loudly and forcefully. She rambled off something in wolof. She tried to hold me down in the chair to give me the injection. I snatched away and again tried to explain. She and Cora both kept telling me no. After a big enough fuss, a man who spoke English came in and translated what I was trying to say. They decided not to give me the shot for malaria, but still gave me a shot, that I later found out was for pain. I was never able to find out exactly what it was.

We made it back to the house and I collapsed in the bed. By late evening, I was beginning to doubt that I had malaria. One of the main symptoms is that your whole body is racked with excrutiating pain. I was weak and dizzy, but not in pain. My hostess decided to call a private doctor she knows that speaks English. (I'm not sure why she didn't mention this before my horrific hospital experience.) We took a taxi and went to her home office. After explaining my symptoms she did a full exam and diagnosed me with a gastrointestinal infection. She prescribed an antibiotic and told me to come back if I wasn't feeling better in two days. Two days later I went back and she sent me to have lab tests and a chest x-ray because I was having trouble breathing. Because getting a taxi and going out took a lot of energy, I decided to wait two days to see if I felt any better. Two days passed with no improvement. I went to the lab and had tests done. Sparing all the gorey details, by the end of the day I had the results and returned to the doctor's for her analysis of the report, which was written in french. The diagnosis: amoebic dysentery. Sounds horrible. Well it was. With the proper diagnosis, she changed my prescription and added iron to the list of pills, since by then I was anemic.

With the change of medication, I felt even worse. Now on top of being weak, sweaty, dehydrated and unable to eat, I was double over in pain. Oh, and just as a safety measure, I was also given a 3-day malaria pill treatment. I was taking so many pills throughout the day that it became my occupation. Some pills required that I eat, which was impossible. I was hating food. It was a battle to keep up the pill regiment. But I knew that I wouldn't get better if I didn't.

By the time I got the proper diagnosis, a week had past. I did nothing all day but lie in bed and when I could focus, I would read. I read any and everything. Whatever was available just to keep from going crazy. By the middle of the second week, I was feeling better, but still too weak to do anything. I knew that I wouldn't have the energy to pack myself into a stiffling hot bus and trek to the next city. I decided it was best to go home. Feeling both disappointed and stircrazy, I knew it would be better to go home and finish recovering there. At least I wouldn't have to be paranoid about everything I ate and drank. After two and half weeks, I was well enough to make the long flight home.

My original plan was to stop in Paris for a few days on the way back. This would have broken up the long flight, but because I was sick, it was condensed into one day. Well, it would have been if I hadn't missed my connecting flight in Paris. I flew from Dakar to Lisbon to Paris to Amsterdam to San Francisco. The flight from Lisbon was two hours late so I just missed the connecting flight in Paris. I stayed the night. I guess I can claim to have been to Paris but I was too tired (and cold) to go out, so my total Parisian experience was a one hour train ride from one airport to the other and the shuttle ride to my hotel. I like what I saw. I'll have to return to both Paris and Senegal.

Monday, October 18, 2004

Sick in Dakar

I arrived in Dakar two weeks ago via plane from Mali and immediatetly became sick. (My new friend here, Angela, insists that I point out that more than likely I got sick in Mali. "Don't blame that on Senegal," she said) At first I was diagnosed with malaria. Seems that is always the first diagnosis for sickness with a fever. But it wasn't behaving like malaria, and lab tests show that I have dysentery.

Unfortunately I have not been able to see Senegal. I also have not been able to finish writing about Mali. But I will! As soon as I recover. Thanks to everyone who has been checking on me!

I arrived in Dakar two weeks ago via plane from Mali and immediatetly became sick. (My new friend here, Angela, insists that I point out that more than likely I got sick in Mali. "Don't blame that on Senegal," she said) At first I was diagnosed with malaria. Seems that is always the first diagnosis for sickness with a fever. But it wasn't behaving like malaria, and lab tests show that I have dysentery.

Unfortunately I have not been able to see Senegal. I also have not been able to finish writing about Mali. But I will! As soon as I recover. Thanks to everyone who has been checking on me!

Saturday, October 02, 2004

What is it with me and taxis?

I arrived in the capital city of Bamako after an eight hour ride on a bus that from the outside looked pretty decent. Displayed prominently on the back window was a decal listing all the amenities: TV/Video, A/C, shaded windows, reclining seats. But as you might guess, the only thing it really had to offer was no a/c and windows that did not open. It was by far the most grueling trek yet. It was so hot that everyone was lulled into a silent stupor and I was nearly comatose the whole way.

When I arrived, my Dogon guide's brother came to meet me at the bus station and take me back to the restaurant they owned. They had a few rooms there, but I decided I didn't like the arrangement. Tired and anxious to find a comfortable place, I got a taxi and tried to recall the little French I had not been using. With gestures and mangled French I asked him to take me to a hotel I'd found in my guide book. He didn't understand, but unlike the last taxi driver, he was determined to help me. He went inside a store and got directions.

As we drove across town, the traffic was so chaotic, that I couldn't recognize who had the right to drive where. All of this mixed with my frustration, that I'm sure the driver could sense, must have made him anxious as well. He seemed lost and confused and I just had to reassure myself that this is not worst situation I've been in.

The further we drove, the darker it became, there were less street lights and less people. I told myself there was no need to panic. The driver realizing he needed more directions, got out and walked back to a guard we had just passed. But in his hurry, he did not put the car in park or put on the brake. I felt the car rolling down the hill. I quickly reached across the back seat to grab the parking brake, but i didn't see one nor could I figure out how to put the car in park. At this point the car was picking up speed, heading down hill and crossing to the opposite side of the street. There was nothing else I could do. I flung open the door and jumped out. I yelled back at the taxi driver and pointed to the car. He ran downhill after the car, jumped in and stopped it before it hit anything. Whew! That was close.

I got back in and we reached the hotel which was just around the corner. I decided to treat myself to some A/C and a little bit of luxury. Instead of going into the hotel from my guide book, I walked across the street to the shiny and bright Le Grand Hotel! I stayed for 4 days, not doing much other than hiding from the heat.

I arrived in the capital city of Bamako after an eight hour ride on a bus that from the outside looked pretty decent. Displayed prominently on the back window was a decal listing all the amenities: TV/Video, A/C, shaded windows, reclining seats. But as you might guess, the only thing it really had to offer was no a/c and windows that did not open. It was by far the most grueling trek yet. It was so hot that everyone was lulled into a silent stupor and I was nearly comatose the whole way.

When I arrived, my Dogon guide's brother came to meet me at the bus station and take me back to the restaurant they owned. They had a few rooms there, but I decided I didn't like the arrangement. Tired and anxious to find a comfortable place, I got a taxi and tried to recall the little French I had not been using. With gestures and mangled French I asked him to take me to a hotel I'd found in my guide book. He didn't understand, but unlike the last taxi driver, he was determined to help me. He went inside a store and got directions.

As we drove across town, the traffic was so chaotic, that I couldn't recognize who had the right to drive where. All of this mixed with my frustration, that I'm sure the driver could sense, must have made him anxious as well. He seemed lost and confused and I just had to reassure myself that this is not worst situation I've been in.

The further we drove, the darker it became, there were less street lights and less people. I told myself there was no need to panic. The driver realizing he needed more directions, got out and walked back to a guard we had just passed. But in his hurry, he did not put the car in park or put on the brake. I felt the car rolling down the hill. I quickly reached across the back seat to grab the parking brake, but i didn't see one nor could I figure out how to put the car in park. At this point the car was picking up speed, heading down hill and crossing to the opposite side of the street. There was nothing else I could do. I flung open the door and jumped out. I yelled back at the taxi driver and pointed to the car. He ran downhill after the car, jumped in and stopped it before it hit anything. Whew! That was close.

I got back in and we reached the hotel which was just around the corner. I decided to treat myself to some A/C and a little bit of luxury. Instead of going into the hotel from my guide book, I walked across the street to the shiny and bright Le Grand Hotel! I stayed for 4 days, not doing much other than hiding from the heat.

Thursday, September 30, 2004

Sevare, Mali

In Sevare, I stayed in a hotel run by a fifty something British woman and her twenty something Dogon husband. I ended up staying here for about a week, mostly trying to recooperate from my hike in Dogon country (and feeling the decline of what I now know was the beginning symptoms of dysentery.) It was so incredibly hot. Hotter even than Dogon country. I thought I had chosen the coolest time of the year. I was wrong. The coolest time is in January and February, when all the tourists converge in masses equal to a transient nation. I was thankful to miss the crowd of "outsiders", but wishing for cooler temperatures.

Sevare is a launching point for many tours, but when the season is slow, it is all but impossible to find a taxi. So I spent most days just lounging in the courtyard at Maison des arts. The British owner was glad to have an English speaker and we spent many hours (me mostly listening) swapping stories of travels and what her life is like here in Mali. She had taken a similar path through West Africa. She too had a disconcerting experience in Ghana and also fell in love with Burkina Faso. But it was Mali that drew her in. Or maybe it was the young man who is now her husband! She shared many intimate details of what it was like to be a British woman living in Mali. To share your husband with another wife. The Dogon family traditions she must learn. The extreme heat and illnesses she has endured.

A crew of two or three men made repairs to the hotel. Because I spent most of the day sprawled in the courtyard, I had a front row seat to the singing of the eldest man on the crew. He had an amazing voice. Mali is known for it's music and this man definitely solidified the acclaim. I think he is a griot. He sang in the traditional style that is a melodious and round chanting sound in a minor key. Some notes would sound to most Western ears to be "off" key. (It is a sound that is common in many Islamic and eastern religions, one to which I have always been drawn.) The exterior corridor where he worked repairing the walls, echoed with the sound of his voice. I tried several time to record him. But the sound of the repairs drowns out his voice. I could have asked him directly, he was very nice. I liked the idea of it being natural, candid, not performed. I'll have to listen again, maybe I can "digitally remaster" the recording to remove the noise.

In Sevare, I stayed in a hotel run by a fifty something British woman and her twenty something Dogon husband. I ended up staying here for about a week, mostly trying to recooperate from my hike in Dogon country (and feeling the decline of what I now know was the beginning symptoms of dysentery.) It was so incredibly hot. Hotter even than Dogon country. I thought I had chosen the coolest time of the year. I was wrong. The coolest time is in January and February, when all the tourists converge in masses equal to a transient nation. I was thankful to miss the crowd of "outsiders", but wishing for cooler temperatures.

Sevare is a launching point for many tours, but when the season is slow, it is all but impossible to find a taxi. So I spent most days just lounging in the courtyard at Maison des arts. The British owner was glad to have an English speaker and we spent many hours (me mostly listening) swapping stories of travels and what her life is like here in Mali. She had taken a similar path through West Africa. She too had a disconcerting experience in Ghana and also fell in love with Burkina Faso. But it was Mali that drew her in. Or maybe it was the young man who is now her husband! She shared many intimate details of what it was like to be a British woman living in Mali. To share your husband with another wife. The Dogon family traditions she must learn. The extreme heat and illnesses she has endured.

A crew of two or three men made repairs to the hotel. Because I spent most of the day sprawled in the courtyard, I had a front row seat to the singing of the eldest man on the crew. He had an amazing voice. Mali is known for it's music and this man definitely solidified the acclaim. I think he is a griot. He sang in the traditional style that is a melodious and round chanting sound in a minor key. Some notes would sound to most Western ears to be "off" key. (It is a sound that is common in many Islamic and eastern religions, one to which I have always been drawn.) The exterior corridor where he worked repairing the walls, echoed with the sound of his voice. I tried several time to record him. But the sound of the repairs drowns out his voice. I could have asked him directly, he was very nice. I liked the idea of it being natural, candid, not performed. I'll have to listen again, maybe I can "digitally remaster" the recording to remove the noise.

Tuesday, September 28, 2004

Mopti taxi

Today I took a taxi from my hotel to the garre sation to catch a taxi brusse (like a tro-tro) to the next town. I walked from my hotel to the junction where taxis stop. I saw a few taxis pass and then decided just to take the next one. It was the typical banana yellow color of taxis here. I'm not sure the exact make and model, but it looked like an old rusted out 1970s era Datsun hatchback.

The passenger and I who were joining the others had to wait for the driver to open the door. The handle was rigged with a string. After letting us in, the driver climbed in and "hotwired" the ignition from two wires hanging below the steering wheel. (I know i've grown accustomed to transport here, because this didn't even phase me. Actually in recent weeks past, I would have passed this taxi all together for being too rusty.)

We started on our way slowly laboring through the narrow streets of old town Mopti. As we turned one corner, I heard a scraping noise from the back left tire where I was sitting. I paid little attention, assuming it was grinding brakes like that of so many other taxis. Just as I noticed everyone in the car turning to look in my direction, I felt the car drop and rock to the left. The wheel had come off! Unbelievable! For once I was glad that the traffic was slow. We all bailed out of the taxi in search of another, leaving the driver to the gawks and stares of all passing by. All I could do was laugh, thinking to myself, no one at home will believe this.

Today I took a taxi from my hotel to the garre sation to catch a taxi brusse (like a tro-tro) to the next town. I walked from my hotel to the junction where taxis stop. I saw a few taxis pass and then decided just to take the next one. It was the typical banana yellow color of taxis here. I'm not sure the exact make and model, but it looked like an old rusted out 1970s era Datsun hatchback.

The passenger and I who were joining the others had to wait for the driver to open the door. The handle was rigged with a string. After letting us in, the driver climbed in and "hotwired" the ignition from two wires hanging below the steering wheel. (I know i've grown accustomed to transport here, because this didn't even phase me. Actually in recent weeks past, I would have passed this taxi all together for being too rusty.)

We started on our way slowly laboring through the narrow streets of old town Mopti. As we turned one corner, I heard a scraping noise from the back left tire where I was sitting. I paid little attention, assuming it was grinding brakes like that of so many other taxis. Just as I noticed everyone in the car turning to look in my direction, I felt the car drop and rock to the left. The wheel had come off! Unbelievable! For once I was glad that the traffic was slow. We all bailed out of the taxi in search of another, leaving the driver to the gawks and stares of all passing by. All I could do was laugh, thinking to myself, no one at home will believe this.

Tuesday, September 21, 2004

Dogon Villages

The first day we left Bankass early. Adding to my modes of transport, we climbed aboard a horse drawn 2-wheel cart which would take us to the first village. We plodded slowly along the long flat road. I wondered at times if the horse was going to make it. Mostly, I was just happy to be out in the open air. It was hot! So hot, like hot I have never felt. In the valleys and lowlands you can see for miles. During this, the rainy season, there is green everywhere. Millet, the main crop, is tall, green and nearly ready for harvest. There are patches of green brush and long wispy grasses dotted across the sandy landscape. Baobab, mango and bissap trees are green and leafy. Occasionally we would see children and woman walking along the road with bails of twigs on their head and cattle grazing in the grasses. But mostly there was no one in site. Quite a contrast from most of the place I had just visited.

Each day we hiked to two villages. In the morning, after a breakfast of limp french bread and instant coffee, we'd start hiking around 7am. By 11 am we'd stop for lunch and rest until 4 pm, waiting for the heat of the day to pass. From 4 to 6 pm we'd hike to the village where we would sleep for the night.

The first day was pretty slow and easy. The terrain was flat and sandy.

After getting off the horse cart, we walked into the first village to see a mud/rammed earth mosque that is typical for this region. We passed a group of elders sitting in the shade of a trellis. This would be my first opportunity to offer the tourist gift of kola nuts. The elder men and sometimes woman in these villages chew the reddish orange kola nut for its stimulant. As a gesture of respect and offering, visitors present one or two kola nuts to all elders they encounter. I carried a sack of nuts that was about the length of my arm from elbow to wrist. Though not particularly big, the space in my day pack was limited. It was already filled with my two cameras, mosquito net, sleep sheet and water. I left my large bag back at base camp.

As we walked into the first village, my guide tried to teach me a few simple Dogon greetings. I couldn't seem to remember anything. Was it the heat? It didn't seem to matter because my simple two word greeting was drowned out by the long greeting that unfolded like a syncopated call and response.

Seyoma?

-seyo

Gineh Seyom?

-seyo

Deh Seyom?

-seyo

Na Seyom?

-seyo

Ulumo Seyom?

-seyo

Awa

Popo

To me it sounded like a chorus of seyo seyo seyo seyo. . .bouncing back and forth between my guide and nearly everyone we passed. The greeting itself takes about 10-12 seconds, so if you are passing someone, both parties slow down or stop so that they are still within hearing distance when the greeting is complete. The greeting is asking "how are you? How's the family? How's your father? How's your mother? and so on. . .the person answers "seyo" which means "fine." This is said if your family is fine or even if your mother is sick. After the greeting is finished, then you discuss the real conditions. I couldn't help but think what life would be like if we at home engaged everyone we saw this way. Although the greeting is definitely a formula, people seem genuinely happy to see one another. You can see people's face light up when it is someone closer to their family. And often men would shake hands and/or hug. Children would stop and stare at me. If I smiled and waved, they would smile from ear to ear and wave "Ca ba!" Translated: ca va. They know to speak french when they see an outsider! Is she African? The old men would ask my guide. He would say "no, she's americaine noire."

My guide is from the village Ende. The second day we reached Ende as a magnificent storm was flashing in the distant sky. It was too hot to sleep inside, but the huge raindrops began to fall sporadically and there was no choice but to go inside. Because of the Harmattan winds, most campements are built with rooms that have no windows, only a door. My room was dark and hot and by the light of the lantern, I could barely make out the images painted on the wall. I sat with the door open and watched the storm. Every few minutes lightening would flash across the sky and give me a mometary glimpse of the room. Just outside the courtyard was a tree that was crammed full with bright white egrets. Everytime the lightening flashed, i could see the black silhouette of the baobab tree covered in little white creatures. It was a very strange sight, like blinking and staring at a strobe light. Am I dreaming? No I am awake. Eventually the rain came. It pelted and poured. But still I kept my door open. I couldn't imagine sleeping in this dark windowless sauna of a room. No, I'd rather deal with any creatures that might find their way into my room.

The next morning, we rose and made a short hike up into the cliffs to see the houses of the Tellem people who proceeded the Dogon.

The first day we left Bankass early. Adding to my modes of transport, we climbed aboard a horse drawn 2-wheel cart which would take us to the first village. We plodded slowly along the long flat road. I wondered at times if the horse was going to make it. Mostly, I was just happy to be out in the open air. It was hot! So hot, like hot I have never felt. In the valleys and lowlands you can see for miles. During this, the rainy season, there is green everywhere. Millet, the main crop, is tall, green and nearly ready for harvest. There are patches of green brush and long wispy grasses dotted across the sandy landscape. Baobab, mango and bissap trees are green and leafy. Occasionally we would see children and woman walking along the road with bails of twigs on their head and cattle grazing in the grasses. But mostly there was no one in site. Quite a contrast from most of the place I had just visited.

Each day we hiked to two villages. In the morning, after a breakfast of limp french bread and instant coffee, we'd start hiking around 7am. By 11 am we'd stop for lunch and rest until 4 pm, waiting for the heat of the day to pass. From 4 to 6 pm we'd hike to the village where we would sleep for the night.

The first day was pretty slow and easy. The terrain was flat and sandy.

After getting off the horse cart, we walked into the first village to see a mud/rammed earth mosque that is typical for this region. We passed a group of elders sitting in the shade of a trellis. This would be my first opportunity to offer the tourist gift of kola nuts. The elder men and sometimes woman in these villages chew the reddish orange kola nut for its stimulant. As a gesture of respect and offering, visitors present one or two kola nuts to all elders they encounter. I carried a sack of nuts that was about the length of my arm from elbow to wrist. Though not particularly big, the space in my day pack was limited. It was already filled with my two cameras, mosquito net, sleep sheet and water. I left my large bag back at base camp.

As we walked into the first village, my guide tried to teach me a few simple Dogon greetings. I couldn't seem to remember anything. Was it the heat? It didn't seem to matter because my simple two word greeting was drowned out by the long greeting that unfolded like a syncopated call and response.

Seyoma?

-seyo

Gineh Seyom?

-seyo

Deh Seyom?

-seyo

Na Seyom?

-seyo

Ulumo Seyom?

-seyo

Awa

Popo

To me it sounded like a chorus of seyo seyo seyo seyo. . .bouncing back and forth between my guide and nearly everyone we passed. The greeting itself takes about 10-12 seconds, so if you are passing someone, both parties slow down or stop so that they are still within hearing distance when the greeting is complete. The greeting is asking "how are you? How's the family? How's your father? How's your mother? and so on. . .the person answers "seyo" which means "fine." This is said if your family is fine or even if your mother is sick. After the greeting is finished, then you discuss the real conditions. I couldn't help but think what life would be like if we at home engaged everyone we saw this way. Although the greeting is definitely a formula, people seem genuinely happy to see one another. You can see people's face light up when it is someone closer to their family. And often men would shake hands and/or hug. Children would stop and stare at me. If I smiled and waved, they would smile from ear to ear and wave "Ca ba!" Translated: ca va. They know to speak french when they see an outsider! Is she African? The old men would ask my guide. He would say "no, she's americaine noire."

My guide is from the village Ende. The second day we reached Ende as a magnificent storm was flashing in the distant sky. It was too hot to sleep inside, but the huge raindrops began to fall sporadically and there was no choice but to go inside. Because of the Harmattan winds, most campements are built with rooms that have no windows, only a door. My room was dark and hot and by the light of the lantern, I could barely make out the images painted on the wall. I sat with the door open and watched the storm. Every few minutes lightening would flash across the sky and give me a mometary glimpse of the room. Just outside the courtyard was a tree that was crammed full with bright white egrets. Everytime the lightening flashed, i could see the black silhouette of the baobab tree covered in little white creatures. It was a very strange sight, like blinking and staring at a strobe light. Am I dreaming? No I am awake. Eventually the rain came. It pelted and poured. But still I kept my door open. I couldn't imagine sleeping in this dark windowless sauna of a room. No, I'd rather deal with any creatures that might find their way into my room.

The next morning, we rose and made a short hike up into the cliffs to see the houses of the Tellem people who proceeded the Dogon.

Mali, Mali, magnificent Mali

What an amazing place this is. I arrived via bus from Burkina Faso one week ago. It was in Burkina Faso that I fell in love with Africa, but Mali. . . Mali is even better!

With a loose plan based on advice from my guide book, I headed to Koro, a town just across the Burkina-Mali border. I was planning to head to Dogon country. I knew I would need a guide and preferably an English speaking one. I had had a cryptic conversation with four French volunteers/tourists on my bus. I needed help translating some of the information in the paperwork at the border. (I must have been distracted by the sound of Eminem blaring from the little transister radio. For a second I was confused. Where am I? Oh that's right, at a little dusty border station in Mali.) At our next stop, they told me they had a guide waiting for them and that I could join them on their 8 day trek if they could negotiate it. By the time we arrived, we decided maybe it would be better if I found an English speaking guide. They said they'd ask their guide for a recommendation. When we unloaded from the bus (imagine a greyhound bus that looked like it had survived a fire and sat through several torrential rain storms, most of it's windows missing) the driver, who knew that I spoke English pointed me to his friend and English guide. The guide for the French group pointed to the same person.

We headed off to a nearby restaraunt and negotiated the arrangements for the trip. Dogon villages are impossible to navigate without a native guide. In addition, the villages are still very traditional, untouched by most modern influences including electricity and running water. Without a guide, no tourist could find their way through the unmarked terrain and through the complex social and caste system, likely offending the elders at every turn.

I had read that it's very easy to pick a guide who isn't qualified. There was a list of questions I was supposed to ask to make sure my guide was capable. But after the bus ride I wasn't too sharp witted, so I had to rely on intuition. We agreed upon 4 days and 3 nights, hiking for about 5 hours a day. The deal included 3 meals, accomodation, photo taxes, and of course the guide. We wrapped up our negotiations just before sunset and joined a taxi brusse {something like a tro-tro} to the next town, Bankass, where we'd stay the night and start out for the villages the next morning.

I was mezmerized by the sunset as we drove ever so slowly along the road, where potholes had long ago become craters so large, that there is no driving around them. You slowly descend into them and out again on the other side. Our trip of 50km or so took nearly 2 hours. Inside the taxi brusse we set a new record for how many people could fit on a seat. The young woman next to me was very fidgety, with her baby on her lap, she managed to find enough room to fling herself around {at the sacrifice of my knees and ribs} and start a music war with a teenage boy in the back. She insisted the driver play her cassette of traditional dogon dance music. But the speakers were shrill and nerve racking and eventually the driver turned off the music. This gave Mr. Youngblood in the back, the opportunity to blast from his full stereo boombox everything from 50 Cent to DMX. Of course I found this as absurd as hearing Eminem at the border and I couldn't suppress my laughter. I turned and asked my guide if they understand the words, he said "No. But they like it anyway."

At about 7 pm, we stopped at a small town along the road to let the muslim men in the taxi get out for their evening prayer. We all got out to stretch. Mr. Youngblood got out too, still blasting 50 Cent. I thought this is so surreal. I am in Mali, I just witnessed a dramatic sunset with long dark shadows and intense colors. I am standing on the side of some unknown road in the dark, there is no electricity. I hear the faint chants of the muslim men saying their evening prayer. I can barely see their light color robes rising and falling as they bow on their mats. And louder than all of this is the sound of DMX echoing through the night air. How very strange. I laughed to myself.